Each month, the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles establishes a thematic playlist for you to experiment an immersive journey in the French musical repertoire of the 17th and 18th centuries. Enjoy the music!

By Julien Dubruque, researcher and editorial director of the CMBV, and scientific director of the program "The French Cantata in the 18th century"

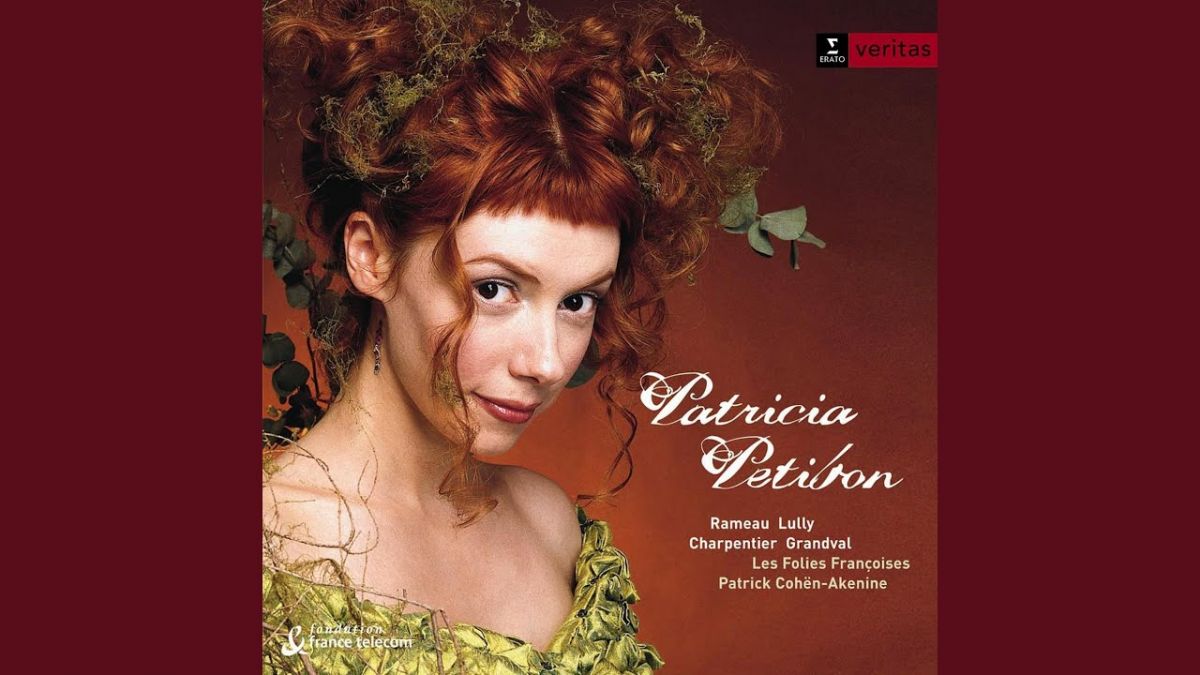

In 2015, the Korean star Sunhae Im included in her first recorded recital the French Orphée by Clérambault and Rameau alongside the Italian Orfeos by Pergolesi and A. Scarlatti.

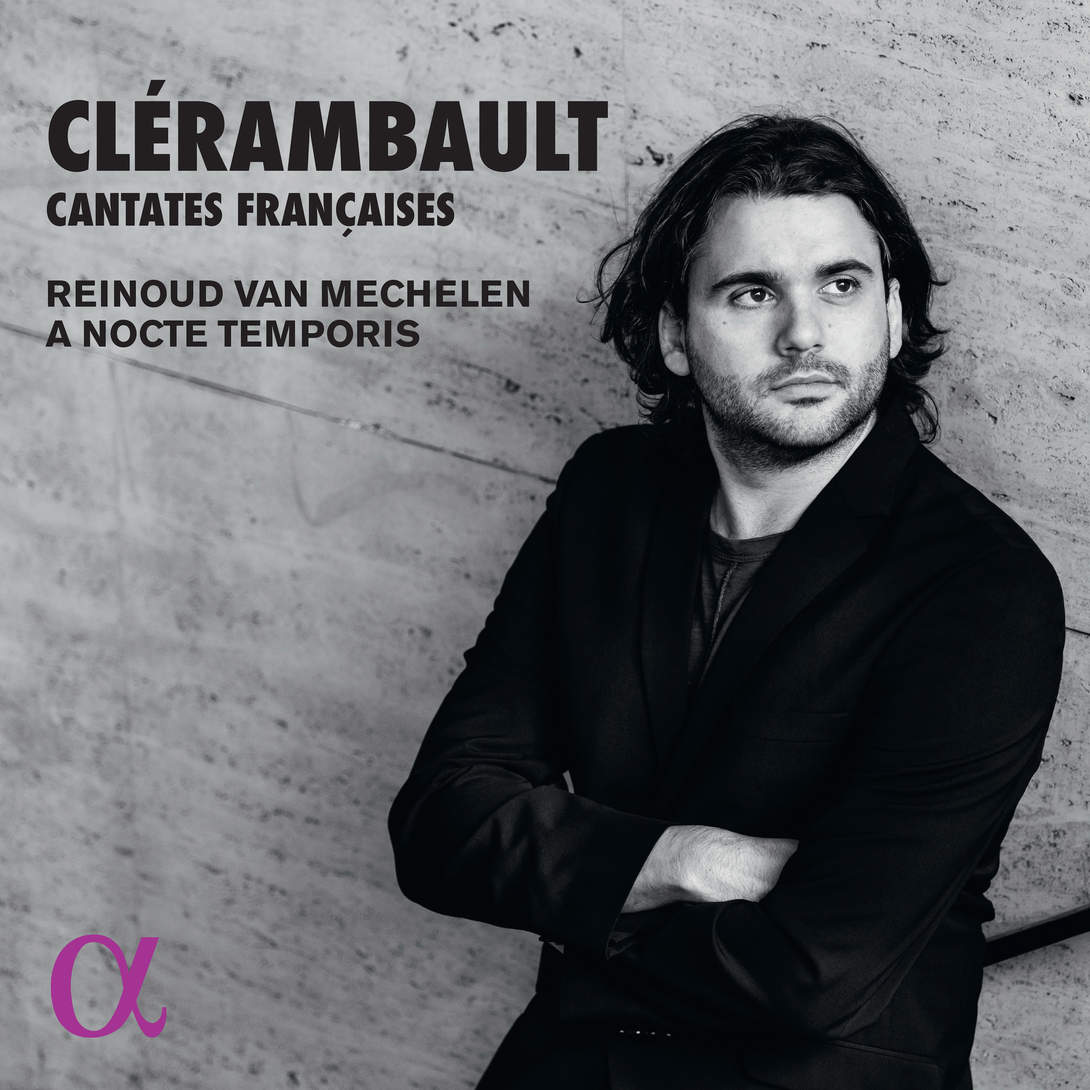

In 2018, one of the most admirable tenors of our time, Reinoud van Mechelen, dedicated his second recorded recital to all the cantatas for haute-contre by Clérambault.

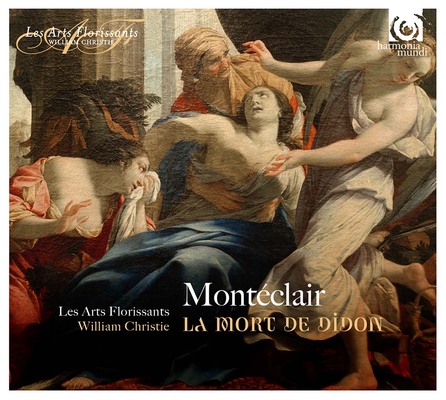

How did we get here? It is stupefying to think that pioneering musicologists like the American Gene Vollen and the Australian David Tunley wrote their comprehensive works on the French cantata in the 1970s almost without having heard it. Clérambault was once a name known only to a few seasoned organists. An important step was taken with the Grandes Journées dedicated to him by the CMBV in 1998, culminating in the publication of Catherine Cessac's monograph. But it is the work of the musicians of the "baroque" revival that has rehabilitated not only the genius that Clérambault was, but also the entire genre of the French cantata, of which he was the most eminent representative. How can we forget the revolutionary recordings that the Arts Florissants of heroic times dedicated to the cantatas of Campra in 1986, and then to those of Montéclair in 1988? Agnès Mellon is still as heart-wrenching.

Among all these pioneers (the complete playlist would take dozens of hours), let us mention with affection Isabelle Poulenard and Sophie Boulin, in a sub-genre, the biblical cantata, in 1986.

For me, it all started exactly twenty years ago at the International Academy of Early Music and Dance in Sablé-sur-Sarthe. As an amateur and beginner harpsichordist, I had come for an entertaining vacation, between a master's degree in Greek history and the aggregation of classical literature, with comrades and friends with whom we spent our time making music instead of studying what we were supposed to study.

At that time, I was still imbued with the prejudices of the typical romantic pianist: that instrumental music was the only serious one, and that if one had to suffer, that the great Bach had composed so much vocal music, there was fortunately no need to pay attention to the generally appalling lyrics of passions and cantatas (like: "Yes, I rejoice in being scourged to death by nettles soaked with your blood, etc."), since it was in German anyway. The idea that one could sing in French seemed to be defended only by Pascal Sevran or Jean Meyrand (here in a cover by Renaud, after his premature death).

In Sablé, I found myself designated to accompany a soprano who was presenting Montéclair's La Mort de Didon. My lack of enthusiasm disappeared as soon as I deciphered the first measures: the beauty of classical French sung suddenly revealed itself to me through a Japanese singer with impeccable diction. During the same workshop, I had randomly borrowed from the conservatory library Jean-Philippe Rameau. Les Boréades or the Forgotten Tragedy by Sylvie Bouissou, which I devoured at night like the detective novel it is. I didn't know it yet, but my destiny was sealed.

The following year, at the Academy of Baroque Music in Amilly, my friends and I naturally arrived with Orphée, the best cantata by Clérambault (see above), and Le Berger fidèle, the best cantata by Rameau.

In Amilly, for the inaugural concert by the professors, Howard Crook chose to perform... Clérambault's Pyrame et Thisbé (see above): I have a vivid memory of this concert and this immense artist — who unfortunately did not record any French cantatas to my knowledge.

In addition to these undisputed masterpieces, among which we should still mention Héraclite et Démocrite by Stuck, which has already been recorded several times.

...there is still so much to discover! Over 1000 printed and manuscript cantatas are still sleeping in libraries. Christophe Rousset has thus had the genius to identify, from a detail of the figured bass, the only cantata by F. Couperin, which was thought to be lost.

Chantal Santon has, to this day, recorded, in a recital, the only number from one of the seven cantatas by Gervais, a composer whose genius is only just beginning to be realized.

Eva Zaïcik also offers, in her debut recorded recital, a magnificent excerpt from Lefebvre, among other rediscoveries.

The genre of the French cantata was so prolific that it gave rise to its own parody, the famous Rien du tout by Grandval.