Each month, the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles establishes a thematic playlist for you to experiment an immersive journey in the French musical repertoire of the 17th and 18th centuries. Enjoy the music !

Playlist by Julien Charbey, publishing administrator of the CMBV

Between the 17th and 18th centuries in France, some of the finest sacred music was written. We need only think of the repertoire of the royal chapel and the creation of the great French motet, with its grandiose architecture, the devotional repertoire, with its touching intimacy, the development of the oratorio, which embraces opera, organ pages, masses, hymns, the Leçons de Ténèbres, meditations, responsories, antiphons, noëls... It is impossible to summarise all the ramifications, development and evolution of this music in all its richness and in the different contexts of the kingdom of France, at court, in the city, in convents, cathedrals, Reims, Dijon, La Rochelle, Bordeaux, Saintes, Clermont-Ferrand, Puy-en-Velay, Lyon, Marseille, Pau, Carpentras, Aix-en-Provence...

This playlist offers a historically chronological and entirely subjective journey drawn mainly from recordings to which the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles has contributed in one way or another throughout its history, varying the composers, performers, musical genres and practices according to the places in which sacred music is embodied.

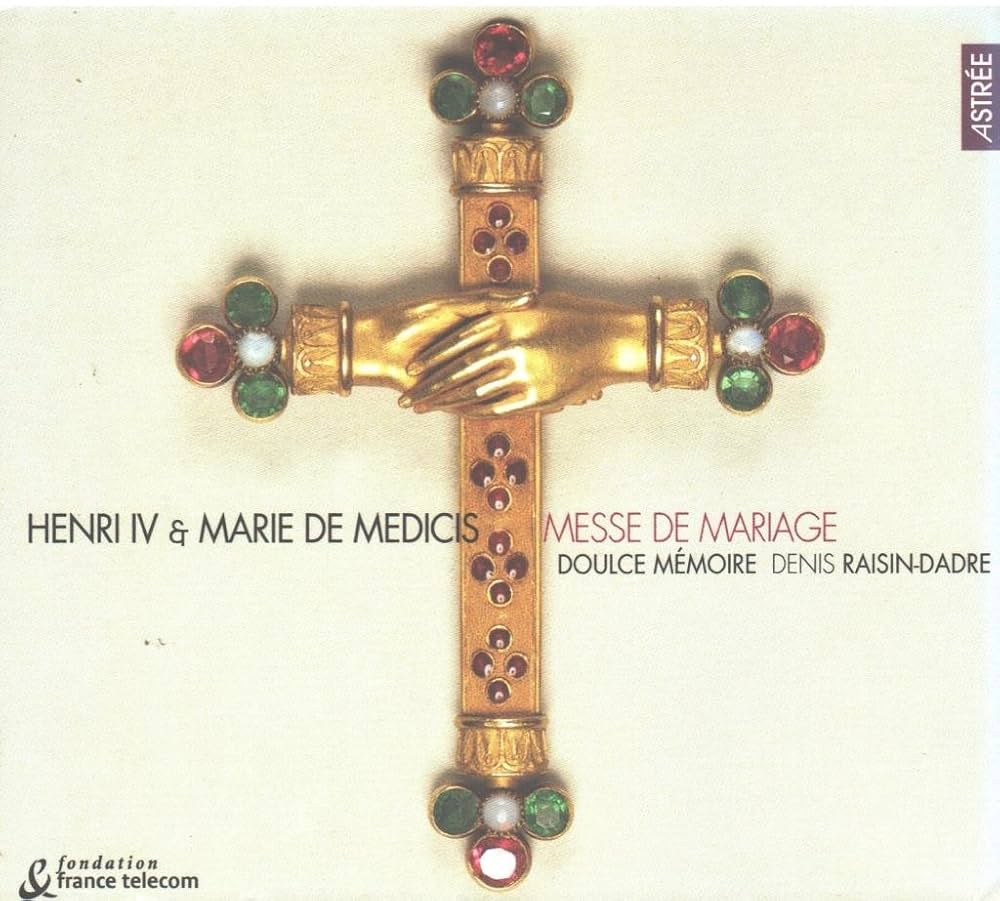

We begin our journey with a Te Deum in French by Claude Lejeune, which could have been given at the wedding of Henri IV, performed here by the ensemble Doulce Mémoire conducted by Denis Raisin-Dadre. In a nod to the dedication of France to the Virgin Mary by King Louis XIII, Guillaume Bouzignac's Marian hymn Assumpta est Maria in a monographic recording by the CMBV choir dedicated to Nicolas Formé, one of the king's favourite composers. Finally, a motet by Antoine Boesset from the CD Meslanges pour la Chapelle d'un Prince recorded by the ensemble Correspondances in 2013, based on the collection by Etienne Moulinié.

Music master in Reims, briefly appointed to Paris Cathedral, François Cosset published his masses with Ballard at the beginning of Louis XIV's reign: beautiful counterpoint, once again brought to life by Sébastien Daucé's Correspondance ensemble. Meanwhile, in the Louvre chapel, long before the king moved to Versailles, a motet by Henry Du Mont, restored to its probable original form, resounds, performed by Frédéric Desenclos's ensemble Pierre Robert. Then Jean-Baptiste Lully offers us a more structured version of the grand motet for extraordinary ceremonies, sketching the beginnings of Versailles with a Miserere probably heard for the first time during Holy Week in 1663 at the Church of Saint-Bernard in the Maison des Feuillants in Paris.

The splendour of music at the turn of the eighteenth century is illustrated by an extract from the celebrated Requiem by Jean Gilles, recorded by Philippe Herreweghe's Chapelle Royale. Michel-Richard de Lalande offers us an example of the great Versailles motet as embodied in the fifth and last chapel of the château, consecrated in 1710. Pierre Tabart, composer at Meaux Cathedral, offers us a more refined vision of counterpoint from the same period, magnificently rendered by the La Fenice ensemble and the Jacques Moderne choir conducted by Jean Tubéry. We then return to the organ in the Royal Chapel at Versailles to listen to the Messe ordinaire à l'usage des paroisses by Couperin le Grand, played by Marina Tchébourkina.

In the city, the great Marc-Antoine Charpentier offers us a choir of great beauty, taken from a sacred story composed for the Théâtre des Jésuites in Paris, Mors Saülis engraved by Gérard Lesne's Il Seminario Musicale. And to mourn the death of Saul, we turn to Michel Lambert's Leçons de Ténèbres, performed by Marc Mauillon.

Jean-François Novelli offers a poignant interpretation of André Campra's motet Nunc dimittis, in which music and song become one and the motet is transformed into a sermon. We join the Demoiselles de Saint-Cyr with the Miserere composed for them by Nicolas Clérambault, here conducted by Emmanuel Mandrin. Henry Desmarest's motet Lauda Jerusalem, addressed as a supplication to the king to obtain his pardon, brings this rich period to a close.

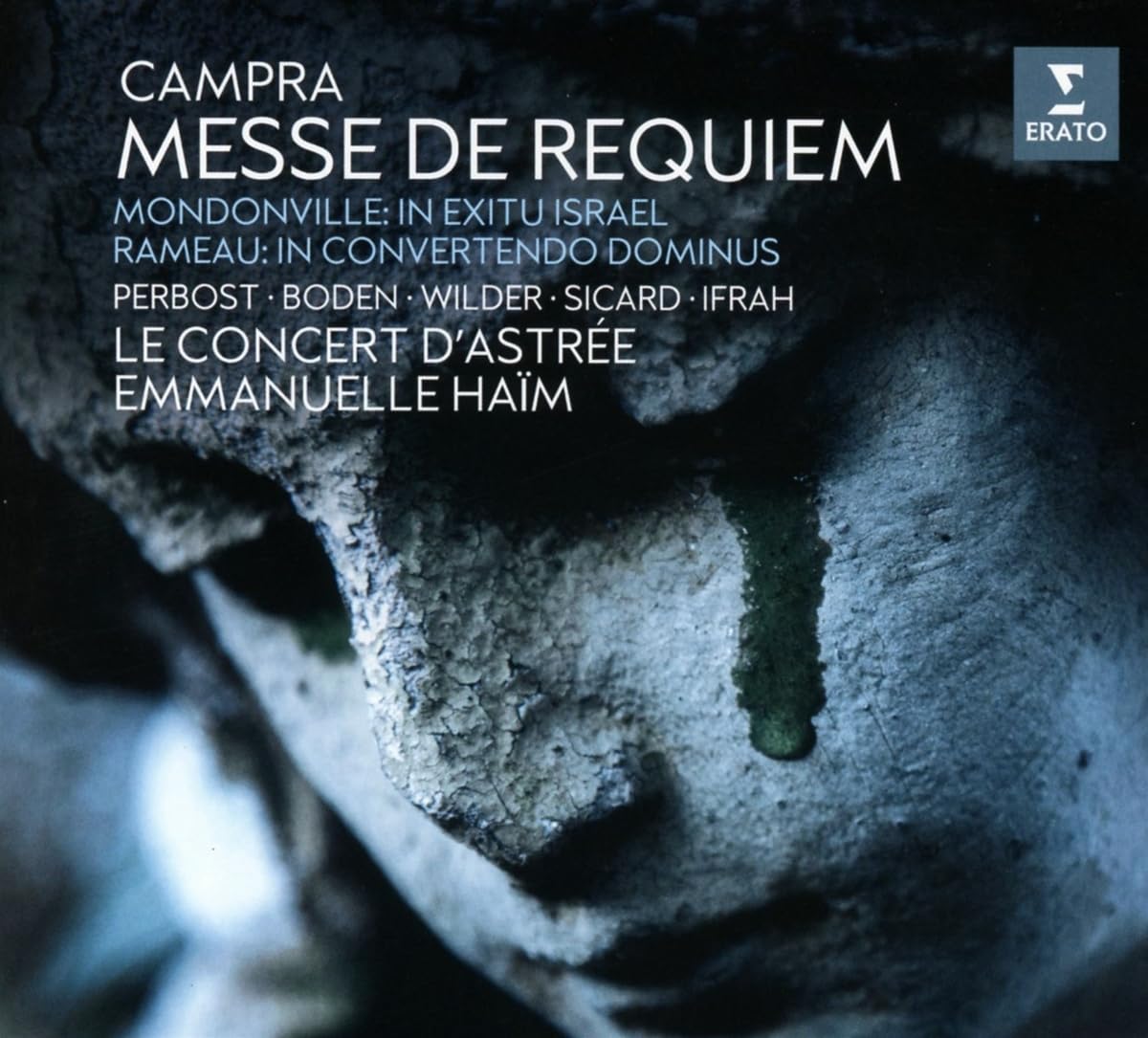

The Regent Philippe d'Orléans, a prince and musician, appointed Charles-Hubert Gervais to the Royal Chapel, whose work we rediscover here performed by the ensemble Les Ombres. During the reign of Louis XV, the grand motet was allowed to leave the liturgical setting. In the provinces, it was performed in concert academies before establishing itself at the Concert Spirituel in Paris. Mondonville gives us a fine example of this in the chorus ‘Le Jourdain retourna en arrière’ from his motet In Exitu Israel, in which the music takes precedence over the power of prayer, performed by Le Concert d'Astrée led by Emmanuelle Haim.

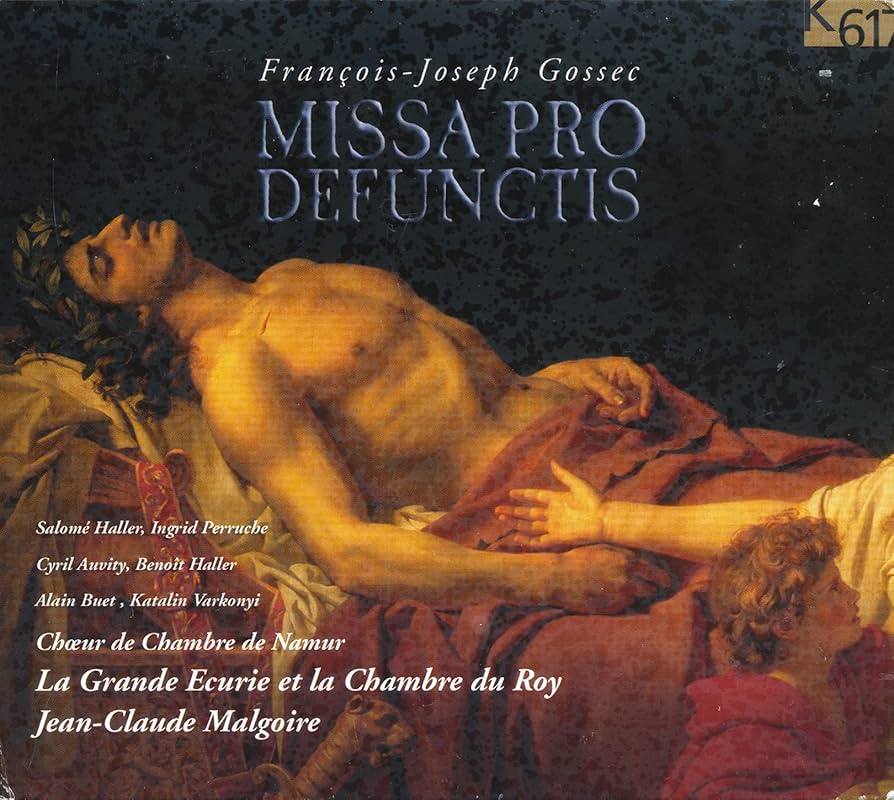

The Age of Enlightenment is drawing to a close. The Tuba mirum from François-Joseph Gossec's Requiem concludes this panorama of two centuries of sacred music in France. It is a perfect illustration of the shift towards classicism and the place that the orchestra took in these works, with its distant brass orchestra that inspired Berlioz, here with La Grande Ecurie and La Chambre du Roy under the baton of Jean-Claude Malgoire.